Secretory Immnuglobulin A (SIgA) is the first antibody isotype that appears in the bodily secretions being detectable at 2 to 4 weeks of age. It is composed of two IgA molecules (dimeric IgA), a joining protein (J), and a secretory component (SC).

The dimeric IgA-J chain complex is produced by B lymphocytes in the submucosal tissues.

The SC is produced by epithelial cells and acts as a receptor for dimeric IgA.

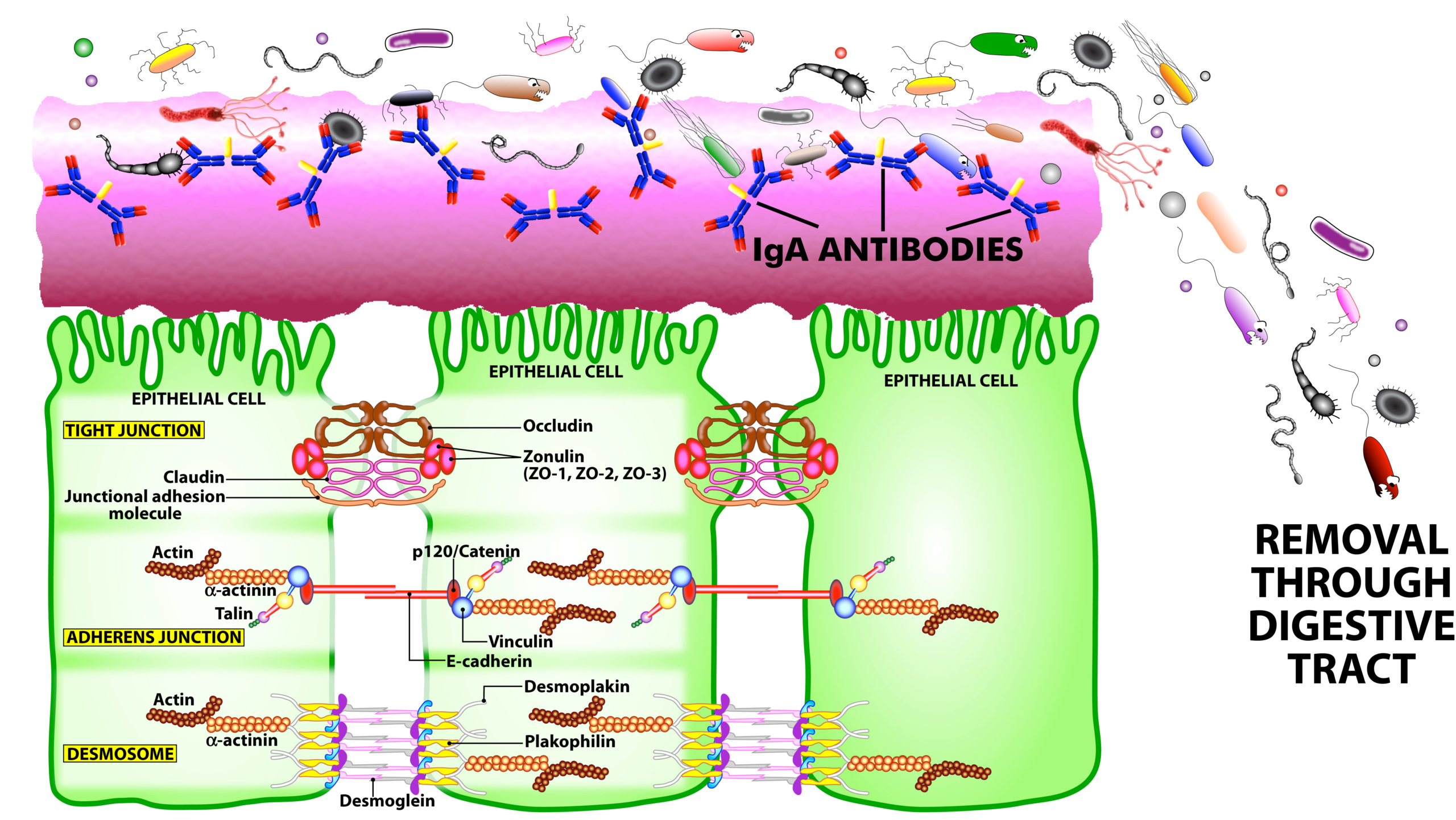

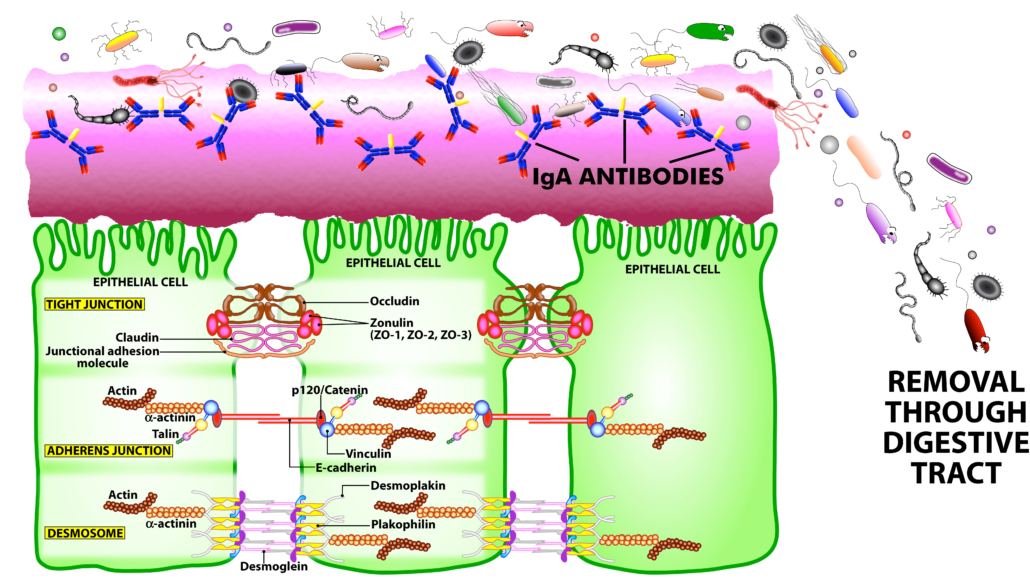

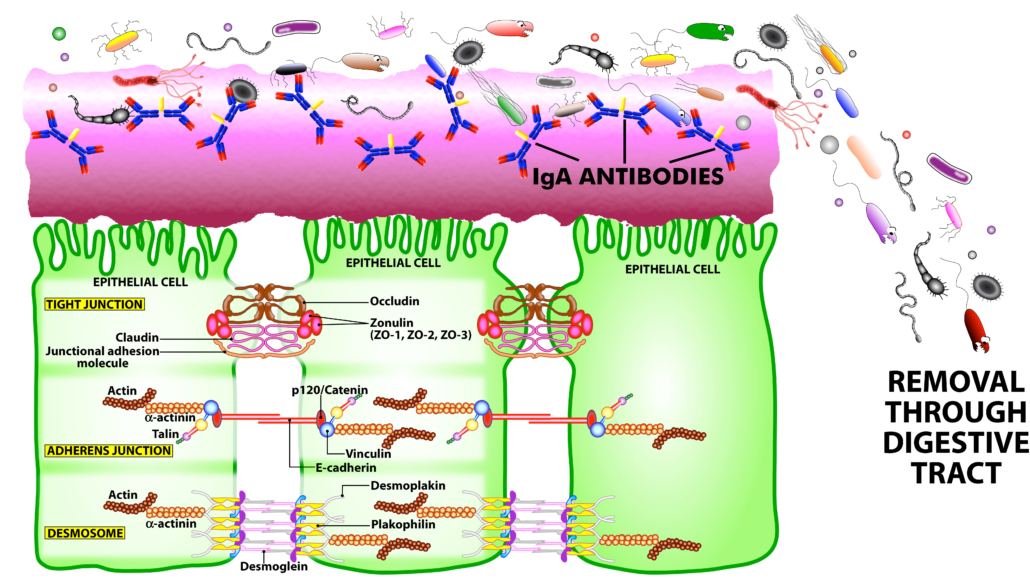

SIgA is the main immunoglobulin found in mucous secretions, including tears, saliva, sweat, colostrum, and secretions from the genitourinary tract, GI tract, prostate and respiratory epithelium. It is the most abundant class of antibodies found in the intestine. It promotes clearance of microbial pathogens and antigens from intestinal lumen through a process of entrapment called “immune exclusion.” SIgA uses this process to prevent the binding of these invaders to the epithelial cell receptors and entrapping them in the upper and lower layers of mucus, thus facilitating their removal through agglutination and GI secretion (see Figure 2).

SIgA also plays a role in maintaining mucosal immune homeostasis through the induction of oral tolerance by promoting the retrotransport of food antigens, bacterial toxins and more across the intestinal epithelia to dendritic cells. This is for the purpose of downregulating the proinflammatory responses that are normally associated with the uptake of these potentially inflammatory and allergenic antigens.

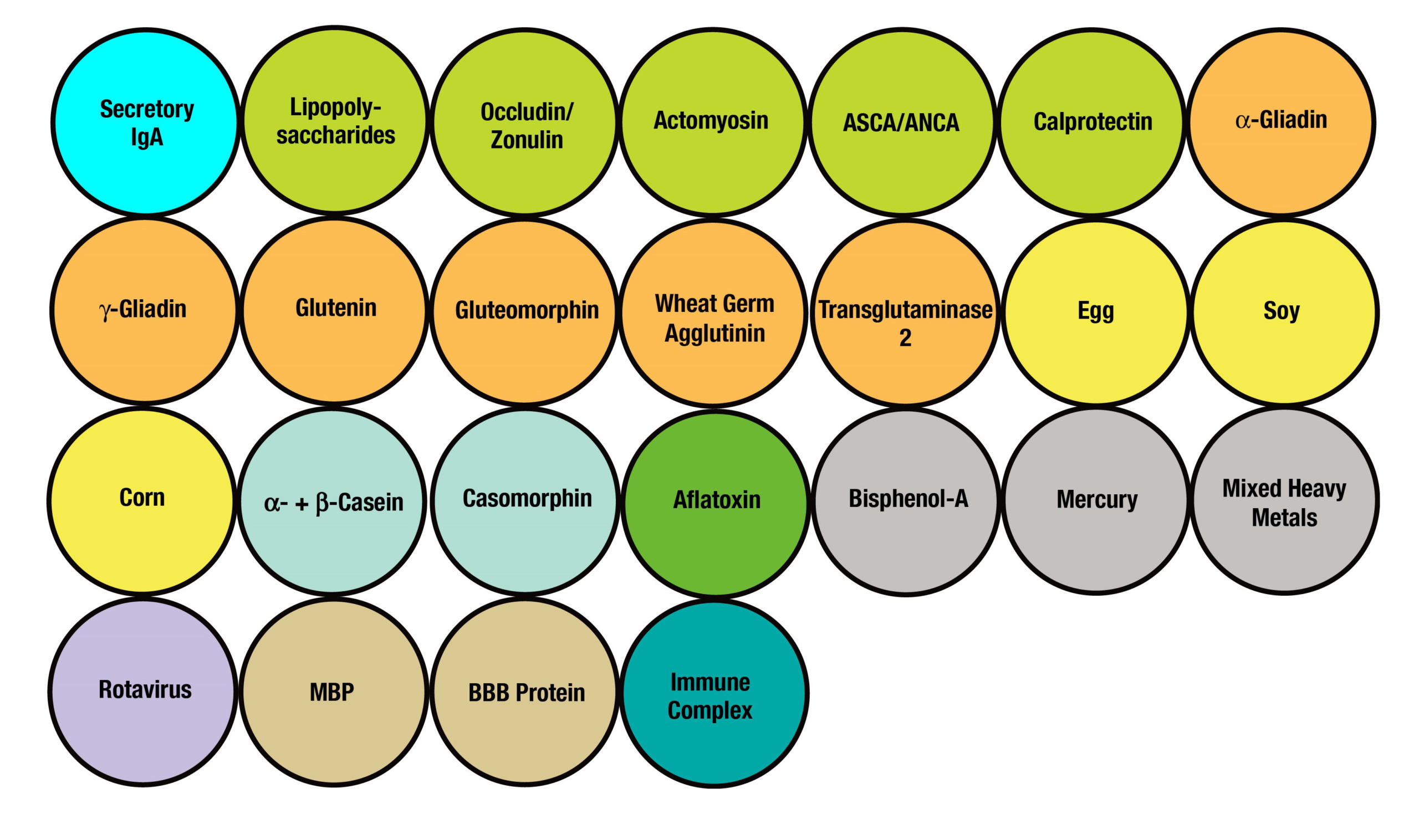

However, when the mucosal immune system is overwhelmed with food antigens, enteric toxins, pathogenic microorganisms and chemical toxicants, the mucosal immune system may lose its homeostasis. This loss of intestinal homeostasis can result in a much higher level of antigens across the epithelium, where the gut-associated lymphoid tissue can transfer the antigens into the circulation.

The presence of these unwanted antigens in the blood results in an immune response consisting of the production of IgA and IgM antibodies against them. These IgA/IgM antibodies acquire their secretory components, then find their way into bodily secretions, including saliva. This phenomenon is called mucosal leakiness to an antigen, which is an early event in the induction of autoimmunity in the gut and beyond.

Figure 2. The immune system’s defensive wall. The mucous membrane or mucosa covers various cavities and internal organs of the human body, including the gastrointestinal tract. It is composed of a mucus layer that contains secretory IgA antibodies, the immune system’s first line of defense. SIgA antibodies catch antigenic invaders through the process of immune exclusion before they can penetrate epithelial cells, and eliminate the unwanted antigens through the digestive system.

SIgA has a wide range of critical functions in the body. These include the following:

- As the first line of defense, SIgA provides a protective wall against harmful viruses, microbes and their antigens.

- Under neuroinflammatory conditions, SIgA secreting cells travel from the gut to the brain with the help of regulatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 to attenuate neuroinflammation.SIgA can neutralize bacterial toxins and the neoantigens formed by toxic chemicals, such as when heavy metals bind to human tissue antigens.

- SIgA can bind to viruses, preventing their Infection, Replication and Spread into the epithelial cells.

- SIgA helps limit the presence of food antigens in the epithelium, thus preventing the initiation of immune response against food and other antigens.

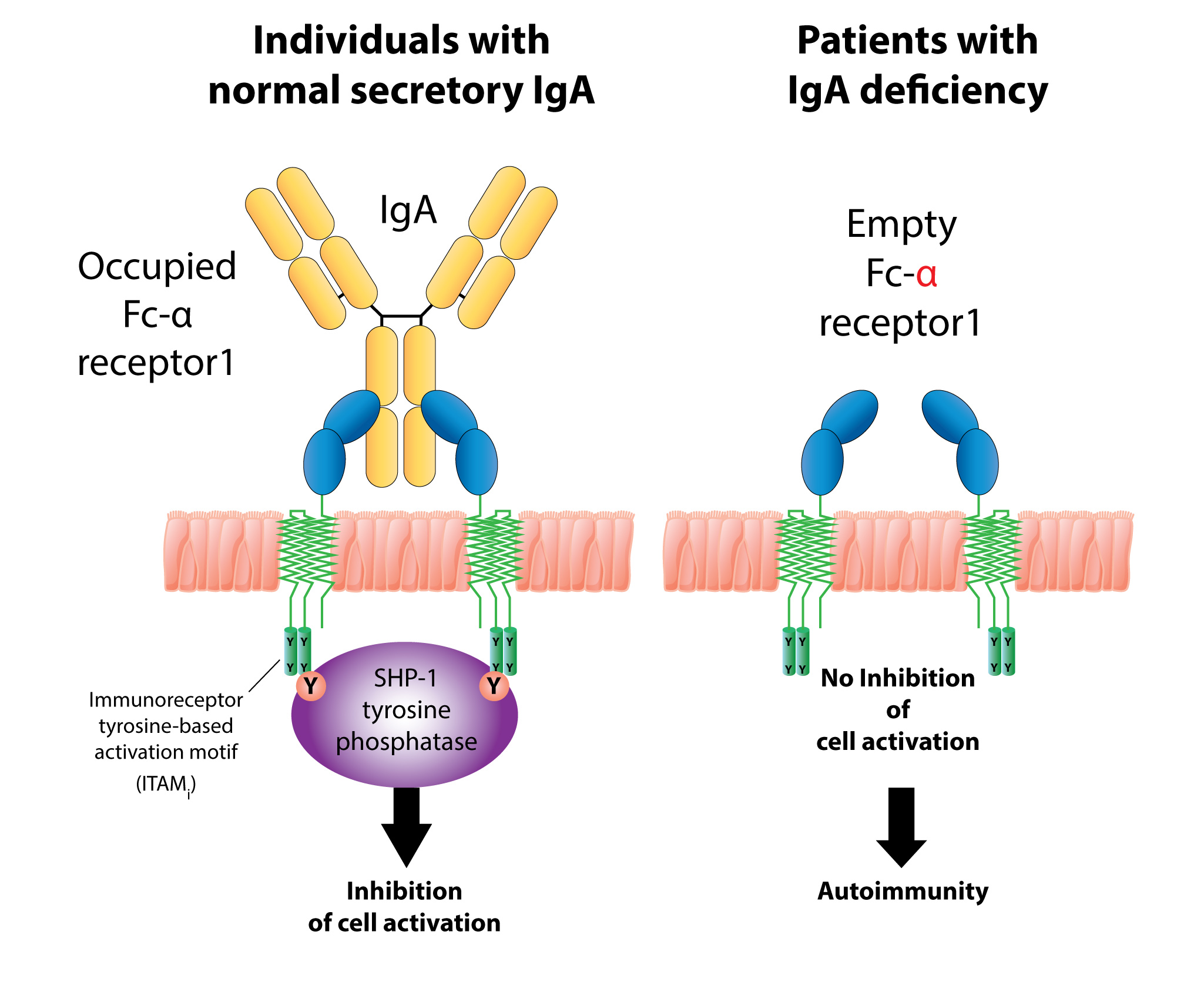

- By binding to a wide range of commensal bacteria, SIgA supports bacterial symbiosis by facilitating or modifying bacterial networks, or by removing them from the GI system.Despite these protective functions of SigA, in the presence of dysregulated gut immune function, breakdown in the oral tolerance mechanism, and large amounts of undigested food or other antigens, the immune system may trigger the overproduction of antigen-specific SIgA, which may contribute towards inflammation and autoimmunity in the gut and beyond.

- The production of high levels of IgA antibodies in saliva against high number or volumes of antigens results in the formation of IgA-immune complexes.

The formation of these food, bacterial toxin, and neoantigen immune complexes may contribute to the failure of oral tolerance, the activation of inflammatory cascade, and the unwanted penetration of food, bacterial toxins and neoantigens into the submucosa and circulation. In addition, immune complexes that are formed by the binding of food antigens, bacterial toxins (LPS, BCDT) or neoantigens to their specific antibodies can bind to a very specific IgA receptor called CD71 on the surface of epithelial cells. This binding of antigen-antibody formations, for example, gliadin-IgA complexes or LPS-IgA complexes, to the IgA receptor may promote the entry of gliadin, LPS or other peptides or antigens through transepithelial transport into the submucosa and into the blood.

The transport of intact peptides through the intestinal epithelium perpetuates inflammatory and immune responses against the penetrating antigens, resulting in the production of IgA and IgM in the saliva, as well as the possible production of IgG (or other antibody isotypes), if the intact antigens or peptides reach the blood.